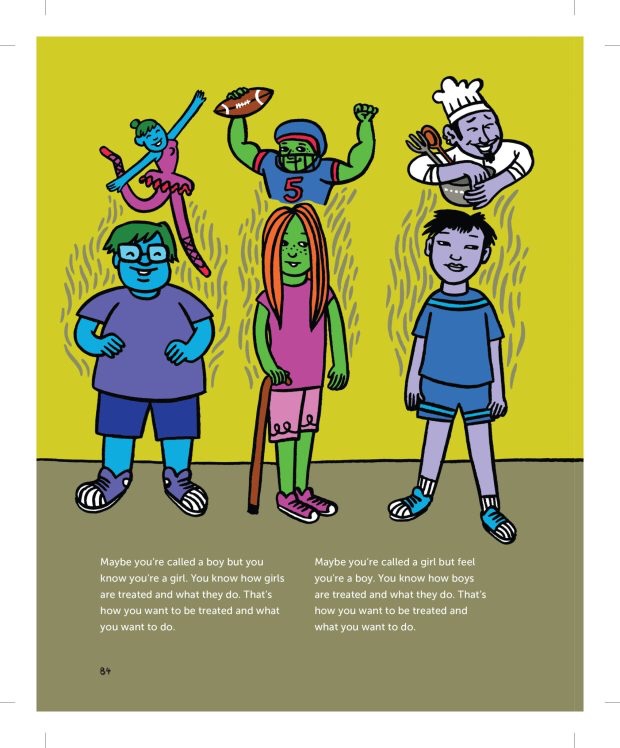

Even as a wider variety of sexual identities and practices are accepted in contemporary American society, the updating of sex education to reflect this new normal remains a controversial subject. While the American Academy of Pediatrics (2018) now advocates for transgender and intersex children to not be forced into gender and sex conformity, warning of the alarmingly high health risks associated with such practices, gender diverse people continue to be ignored in sex education. When public school sex education is recognized as insufficient and detrimentally binary, some parents turn to children’s books considered progressive as a tool to aid in sex education at home. However, even award-winning children’s books on the subject still impose a gender binary as normal. Sex is a Funny Word by Cory Silverberg (2015) is one such highly praised contemporary text (American Library Association, 2016; The Canadian Children’s Book Centre, 2016). An admirable aspect of this text is that Silverberg positions sex education as an open-ended conversation, a way for caregivers to discuss issues of gender and sexuality in a body-positive, inclusive way. However, the “Bodies” chapter, which explores what it means to be called a boy or a girl, is problematic in its essentializing of gender in examples and prompts for the caregiver and child to discuss. I will interrogate the implicit enforcement of gender as binary in Sex is a Funny Word, and suggest ways to push the text further in the right direction.

Silverberg’s text emphasizes the idea of gender as a binary being the norm even while stating that it shouldn’t be. The majority of the chapter presents great scenarios to interrogate our understanding of gender and sex, and its importance. He often frames a gender and sex binary as what is normal by presenting it first, i.e. as the standard (see p. 9). By framing trans, intersex, and genderqueer people as divergent, Silverberg misses the importance of implicit power relations as illustrated by Foucault (1979) by way of Martin (1998) in enshrining oppression. Martin explicates Foucault on the subject explaining, “Gendered (along with “raced” and “classed”) bodies create particular contexts for social relations as they signal, manage, and negotiate information about power and status […] Bodies that clearly delineate gender status facilitate the maintenance of the gender hierarchy” (Martin, 1998, p. 495). The significance of getting the concept of gender right in children’s sex education cannot be overstated as there is social control implicit in gendering. Martin contends that “[t]he gendering of children’s bodies makes gender differences feel and appear natural, which allows for such bodily differences to emerge throughout the life course” (Martin, 1998, p. 495).

It is not accurate to present a binary biological definition of gender because there are in fact multiple, varied, and sometimes oppositional theories of gender (Fixmer-Oraizz & Wood, 2019). Queer performative theorists argue that gender and sex are social constructs (Henningsen, 2016; Fixmer-Oraizz & Wood, 2019), shorthand that makes certain things easier or faster to communicate. Interpersonal theories of gender argue that kids don’t know how the world is; they learn how the world is from their interaction with others (Fixmer-Oraizz & Wood, 2019). According to standpoint theorists, the stories we tell about the world frame their viewpoint for a long time (Fixmer-Oraizz & Wood, 2019). For there to be hope that our nation’s children have a more equitable future than our present, we must strive not to imbue such important conversations with the prejudice and stigmatization we currently encounter. For this reason, I think it’s particularly important to remove biased language in educational texts as much as is possible. Discussing sex and gender as a binary is what makes it so, in defiance of the diverse reality of human bodies (Fausto-Sterling, 1993).

In this way, we can understand how the gender binary is reasoned to be biological even though modern research has proven, as Alice Dreger notes in her Ted Talk (2011) that “sex can come in lots of different varieties.” While many medical professionals such as the doctors and midwives mentioned by Silverberg (2015, p. 10) do, as the book states, “call the baby a boy or girl based on what they see,” the authority to do so ought be questioned. Kim Klausner notes in “Exploding the Binary System” that “the medical profession […] uses its authority to enforce particular power relations” (1997, pp. 185). As Costello elucidates in his “Trans and Intersex Children: Forced Sex Changes, Chemical Castration, and Self-Determination” (2016a), this blind authority given to medical professionals to dictate sex has allowed intersexual bodies to be deeply violated and in many cases irreparably harmed. As Dreger (2011) explains, “in many cases people are perfectly healthy. The reason [intersex bodies] are often subject to certain kinds of surgeries is because they threaten our social categories.”

The discussion of intersex genitalia in Silverberg (2015, p. 9) is thus biologically incorrect in presenting the idea of a gender binary as standard. Costello, an intersex trans man himself, shows in “Intersex Genitalia Illustrated and Explained” (2016b) the diversity of genital formations. Furthermore, there are in fact many reasons why a body is considered intersex beyond genitalia, as Costello (2016c) points out in his “Five Myths that Hurt Intersex People.” Children’s sex education texts should state that bodies come in myriad forms, that genitalia called male or female have analogues parts, and so the sexing of bodies is complex because it does not come down merely to what is in between a one’s legs or even one’s genetics (Dreger, 2011; Costello, 2016). The book could then segue into a discussion of gender, defining it as different and separate from sex. Dreger (2011) contends, “We now know that sex is complicated enough that we have to admit nature doesn’t draw the line for us between male and female or between male and intersex and female and intersex—we actually draw that line on nature.”

In conclusion, to not further oppression by means of gender and sexuality we must avoid enforcing the concept of cisgender heteronormativity as natural. The gender and sex binary must be presented as a social construction and collaborative definitions ought to be offered to describe gender and how gender is deployed in our society. Intersex bodies must not otherized as a third rare option, but presented as part of the wonderful diversity of human anatomy (Dreger, 2011). This is especially important in children’s literature, as it is in childhood when the construction of gender and sexuality begins (Martin, 1998). For all children to have the opportunity for a bright future, all bodies must be honored equally.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2018). Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics, 142(4). Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2018/09/13/peds.2018-2162.full-text.pdf

American Library Association. (2016). 2016 Stonewall Book Awards Announced [press release]. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2016/01/2016-stonewall-book-awards-announced

Costello, C. G. (2016a). Trans and intersex children: Forced sex changes, chemical castration, and self-determination. In E. Gathman (Ed.), Women, health, and healthcare. (pp. 109-112). [Bookshelf Online version]. Retrieved from https://online.vitalsource.com. (Original work published nd.)

Costello, C. G. (2016b). Intersex genitalia illustrated and explained. In E. Gathman (Ed.), Women, health, and healthcare. (pp. 107-108). [Bookshelf Online version]. Retrieved from https://online.vitalsource.com. (Original work published nd.)

Costello, C. G. (2016c). Five myths that hurt intersex people. In E. Gathman (Ed.), Women, health, and healthcare. (pp. 107-108). [Bookshelf Online version]. Retrieved from https://online.vitalsource.com. (Original work published nd.)

Fausto-Sterling, A. (1993). The five sexes: Why male and female are not enough. The Sciences, 33, 20-24.

Fixmer-Oraiz, N., & Wood, J. T. (2019). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Klausner, K. (1997, January). Exploding the binary sex system. Sojourner: The Women’s Forum (Vol. 7, pp. 7-8).

Martin, K. (1998). Becoming a Gendered Body: Practices of Preschools. American Sociological Review, 63(4), 494-511. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2657264 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.

Silverberg, C., & Smyth, F. (2015). Sex is a funny word: a book about bodies, feelings, and YOU. New York: Oakland: Seven Stories Press.

The Canadian Children’s Book Centre. (2016). Winners announced for the 2016 Canadian Children’s Book Centre Awards. Retrieved from: http://bookcentre.ca/2016-ccbc-award-winners/